Brazil - A 21st Century Breakdown (Part 1)

"The best team I played in was the Brazilian one in 2002... It was a team without any vanity, or individuals."

29th June 2002. It’s the eve of the World Cup final and the place we start our story.

Brazil are set to face Germany, a match-up that will come to define both the highs and the lows of this tale. Brazil have dispatched every opponent in their path including a spirited England side 2-1 in the Quarterfinals.

However bar an unfortunate draw to the Republic of Ireland (the only game they have conceded a goal in so far), Germany have quite easily done the same.

It’s not going to be an easy game, but this isn’t ‘just a final’ for Brazil. Yes, they’ve been in this position six times before, winning four, but there’s something deeper under the surface.

And to truly understand the mindset of the Brazil Camp in these moments we’ve got to rewind four years.

2002 should be Brazil’s ‘repeat’, their back-to-back victory on the world stage, but events that are still unexplained to this day derailed their 1998 campaign.

The official story circulated at the time, Ronaldo had suffered an injury during the day and would, unfortunately, be unavailable for the final.

The reality however is much more terrifying.

Joga Bonito, the beautiful game, was the phrase that best characterised Brazil in 1998, they went through their opponents like a footballing tsunami, embodying the true essence of how the game should be played.

They had coasted to the final and were heavy favourites to overcome a strong France side. And at the centre of it all was a 21-year-old Ronaldo.

After lunch on the eve of the final, Ronaldo would return to his room and while taking a nap would experience multiple convulsions. He would explain in his own words to FourFourTwo many years later:

“I decided to get some rest after lunch and the last thing I remember was going to bed. After that, I had a convulsion. I was surrounded by players and the late Dr Lidio Toledo was there. They didn't want to tell me what was going on.

“I asked if they could leave and go talk somewhere else because I wanted to sleep. Then Leonardo asked me to go for a walk in the garden in the hotel where we were staying and explained the whole situation. I was told that I wouldn't play in the World Cup final.”

Conspiracy theories ranging from Brazil throwing the World Cup to Ronaldo being poisoned have raged since the revelation, but what was weird is that after all that ‘Il Fenonemo’ would start the game (a separate conspiracy theory was that Nike forced Ronaldo to play and this isn’t helped by the fact there was a parliamentary enquiry into the claims).

Playing Ronaldo would prove to be fruitless.

John Motson, the English commentator for the final, would go on to say, "He went through the motions of playing centre forward. But certainly, he made no impact on the game."

In fact, his impact probably erred on the side of negativity given that he was the player tasked to mark Zinedine Zidane on corners, and the Frenchman went on to score from two that day.

In James Mosley’s book, Ronaldo: The Journey of a Genius, the team doctor Lidio Toledo said of the events that led to Ronaldo taking the field:

“The tests had thrown up nothing. He’d had tests from a neurologist, a cardiologist, and taken a full electrogram. Many, many tests, but none of them presented anything. Ronaldo wanted to play, but we told him to hang on while we [the CBF medical staff] went off to discuss the situation. He pleaded with us, saying, ‘Lidio, I’m OK. Brazilians need me and I need to play this game, it’s important to me, it’s important to everyone. I have to play.

“Ronaldo then turned around to Zagallo and said, ‘Coach, I’m going to play, even if we have to play with 12, I’m going to play. I’m going on that on that field no matter what.’ He seemed fine. He was coherent, forthright and he seemed fine. We decided to let him play and that’s when he was reinstated on the team sheet.”

Manager Mario Zagallo would defend his decision down the line, stating that not picking Ronaldo in the biggest game in football would invite unnecessary pressure on the national team, especially after the striker returned from the clinic asking to play:

"Faced with this reaction, I chose Ronaldo. Now was it his being chosen that caused Brazil to lose? Absolutely not. I think it was the collective trauma, created by the atmosphere of what had happened.”

Emmanuel Petit scored late confirming a 3-0 victory for France and a World Cup win on home soil, and the Brazilian team returned to a country that wanted to know ‘What the hell happened?”

The inquest into Nike’s involvement in team selection and furthermore into corruption within the Brazillian football federation (CBF) raged on.

Nike would eventually be cleared of any wrongdoing, but the investigation into the CBF found that between 1997 to 2000, the CBF’s budget to invest in grassroots football went from 55% to 37%, while revenues went up four times and so did the directors’ salaries. This cast doubt on whether Nike’s money was being used effectively (now remember this).

In 2001, the Brazillian senate would describe the CBF as ‘a den of crime, revealing disorganization, anarchy, incompetence and dishonesty.’ The organisation would plead its innocence but its reputation was in tatters, it needed to rebuild it the only way it knew how, on the football field.

In terms of the players, as Harvey Dent says in The Dark Knight: ‘You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain’.

Brazilians intensely love football, but that intensity goes the other way when they are dealing with a disappointing defeat. Ronaldo was hounded by the media and made to feel like a scapegoat for Brazil’s failure to win. He told the press at the time:

“I think there’s been a big exaggeration in all this. I want more respect. I’m not a fugitive and I don’t want to be chased every time I go to my mother’s house. I’m trying to lead a normal life as far as possible. I don’t want to be chased anymore.”

So four years on, Brazil needed a win. Not only could they not afford to let their latest golden generation pass without a World Cup to its name, but they needed to rebuild their reputation as one of the pillars of the footballing world.

It feels redundant to explain just how good Brazil were in 2002 as their legend proceeds them. I will however try and paint a picture.

While their performance at the World Cup was something to behold, their qualification form had been less than ideal; the mess of drafts and spoiled canvas that many do not see before the artist finally paints his masterpiece.

Ronaldo had been ruled out for the majority of Brazil’s qualifying campaign after two successive ‘patella ruptures’ (to put it simply his knee had exploded twice, the second being particularly nasty) and a hamstring injury, and in his absence the striking duties would be shared between veteran strikers Romario and Rivaldo.

In his absence, Brazil came third in CONEMBOL Qualifying with 30 points, only officially confirming their place on the final matchday (though it would have taken a catastrophic swing in goal difference to see them drop out of the four qualifying spots).

It wasn’t all because Ronaldo wasn’t available, Romario and Rivaldo would score eight goals each. But the former would be dropped by manager Luiz Felipe Scolari for the main competition.

The reason? Romario had withdrawn from Brazil’s disastrous 2001 Copa America campaign where they had fallen foul of Honduras in the Quarterfinals. The veteran striker had stated that he needed to have an eye operation, but instead went on to play friendlies for Vasco de Gama and then go on holiday. Scolari simply said of the decision:

"People forget the details, but I do not. I almost got fired from the national team after [the Copa América]."

‘Big Phil’ as he’d come to be known, was appointed five matches before the end of the aforementioned hard-fought qualifying campaign, with Brazil in danger of missing out. He succeeded a succession of three managers in three years.

Scolari had made his name employing the 4-4-2 formation in the Brazilian leagues and Saudi Arabia, but in his first game against Uruguay, he chose to adopt a more experimental 3-4-1-2, allowing Cafu and Roberto Carlos free roles on the flanks to attack. They lost 1-0.

Fast forward to the World Cup and the formation was the same, but the personnel had drastically changed. Marcos still stands between the sticks, but with Lucio, Edmilson and Roque Junior (the only survivor in the back three) in front of him instead.

Edmilson is often overlooked key piece in this side. The man who was currently sitting in the centre of Brazil’s defence had been playing as a defensive midfielder in Lyon for the past two years.

In fact, the season before this tournament he had partnered fellow Brazilian Juninho in midfield to win Olympique Lyon’s first league title in their history (Lyon would go on to win seven in a row, three of which Edmilson was part of).

So why he is deployed in defence in favour of Kleberson and Gilberto Silva in midfield? Well, that’s because although Edmilson is listed as a defender on the team sheet, that is far from his role in this side.

‘Mercurial’ is a phrase usually reserved for attackers, but Edmilson's style of play would force his way into the conversation. Picking the ball up deep he would carry it into midfield and pass it off to either one of the pivot, the wingbacks or attackers, but instead of retreating, he would carry on charging forward (this would lead to him scoring an overhead kick vs Costa Rica).

As Richard Williams would write in the Guardian at the time:

“When the elegant Edmilson Jose Gomes de Moraes moves forward with the ball at his feet, what we are seeing is more than just another centre-back suffering from the illusion that he is a reincarnation of Franz Beckenbauer. This is one of those times in the game's history when a single player has the potential to make an adjustment to the way the game is played.

Like the Flying V in the 1992 movie ‘The Mighty Ducks’, Brazil would blitz forward in formation and overwhelm their opponents with defence being an afterthought, Cafu and Roberto Carlos adding even more width.

The team was strangely labelled ‘conservative’ (Brazil’s high expectations shining through) by some, maybe due to the two water-carrying midfielders, Silva and Kleberson. But a better description would be efficient; every move had meaning and was made with intention.

And spearheading this was the Three Rs: Ronaldinho, Rivaldo and of course, R9, Ronaldo.

Ronaldinho would score two goals in the tournament and Rivaldo five, but going into the final Ronaldo was on six goals leading the Golden Boot standings ahead of his team-mate and Germany striker Miroslav Klose.

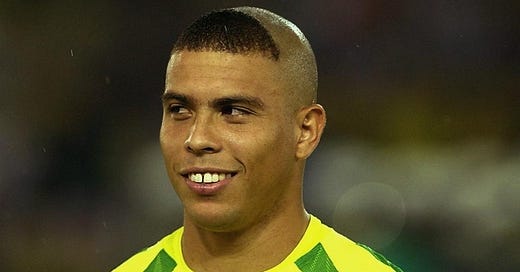

This was his redemption tour, his comeback. After years of sitting on the sidelines injured at Inter Milan and the disappointment of 1998, it was his time once again… and he was doing it with the single stupidest haircut you will ever see in your life.

With a triangle etched into his scalp and a cheeky grin, defence after defence fell to his quick footwork and powerful bursts of pace. Journalist Tim Vickery would write during the tournament:

"Without Ronaldo, Brazil were a shambles, fortunate even to get to the tournament. With him, it was a different story."

However if Ronaldo was the unstoppable force, standing between him and World Cup glory was the immovable object, Germany goalkeeper Oliver Kahn.

Spoilers, Kahn would go on to win the Golden Glove (this was already confirmed before the final) and the Golden Ball for his performances throughout the competition. He was the best keeper in the world and everyone knew it.

Both teams made one change ahead of the match. For Germany it was forced as Michael Ballack was suspended (this made things an uphill battle in midfield for the European side) and Ronaldinho returned after suspension for Brazil.

The first half ended 0-0, but it wasn’t without skirmishes between Ronaldo and Kahn.

Ronaldo’s first chance was a 1-on-1… he shot wide. Then in the 29th minute, he found himself in a similar situation, but Kahn saved his shot easily. And finally is stoppage time, Roberto Carlos found Ronaldo again, but the German keeper saved his shot with an outstretched leg.

Kleberson also had two chances to score, but hit the bar with one and put the other wide. The aura of Kahn was undeniable, it seemed like he was 9ft tall with arms like tree trunks the way that Brazil were consistently trying and failing to aim for the corners to get past him.

But although Kahn was winning the battles, he would not win the war.

Shots from both sides punctuated the early stages of the second half but no one could find the go-ahead goal.

And then it happened, Kahn crumbled.

67th minute, Ronaldo wins the ball of Dieter Hamman in the midfield and surges forward. He finds Rivaldo who strikes it low and firm towards the goal… and Kahn spills it.

The stadium seemingly went silent as the ball bounced away from Kahn who had a look of fear across his face for one of the only times in his career because he could see like everyone else, that the rebound was heading straight to Ronaldo.

He commendably was able to get up and try and muster a save but it was to no avail, the Brazilian striker finally seeing the chink in the German’s armour blasted it past him before he could get to his feet. Kahn later lamented the incident:

"It was my only mistake in the finals. It was 10 times worse than any mistake I've ever made. There's no way I can make myself feel any better or make my mistake go away."

The score was 1-0 and Ronaldo, with one hand firmly around the Jules Rimet, wasn’t going to let it go.

12 minutes later they confirmed their victory. As I said earlier, when Brazil attacked it was like the Ride of the Rohirrim, you felt the momentum shift in an instant in their favour.

Kleberson collected the ball in Brazil’s half and after a bursting run across the halfway line, Brazil had four attackers to Germany’s three defenders. You can see the moment they realise ‘We outnumber you’.

Kleberson passes it to Rivaldo and just as you think Germany might have a small chance to stop the attack here, Rivaldo lets it go.

With one action Rivaldo performs a ‘leap of faith’, for by letting the ball run between his legs it doesn’t end up at his feet, it ends up at Ronaldo’s.

Forward Gerald Asamoah has inexplicably managed to get back to defend the attack, making an admirable attempt to block the shot, but he is not defending a mere man, he is defending ‘Il Fenomeno’.

Ronaldo almost anticipating that a player is running behind him to block the shot calmly takes a touch forward and side-foots it into the corner of the net past Kahn.

Brazil wins the World Cup 2-0, and their redemption is complete. Ronaldo’s redemption is complete. The striker said of the victory:

"I've said before that my big victory was to play football again, to run again and to score goals again. This victory, for our fifth world title, has crowned my recovery and the work of the whole team."

Ronaldo owed a lot to the medical staff who helped him recover from his knee injury in time for the 2002 World Cup and he never forgot it. Gerard Salliant, the surgeon who had operated on his knee was his guest in the crowd for the final. He also thanked the medical staff again when he accepted his third FIFA World Player of the Year award later that year.

I’ve spoken a lot about Ronaldo in this section, but this was his World Cup. Everyone played their part but without Ronaldo, I doubt that they would have won their 5th trophy.

Marcos, Edmilson, Cafu, Roberto Carlos, Kleberson etc. every single player played their part, but if they were the boosters, Ronaldo was the rocket heading for the stars.

Ronaldo would go on to say in 2017 in an interview with Fox Sports, a few years after his retirement:

"The best team I played in was the Brazilian one in 2002, we felt that we could always score. It was a team without any vanity, or individuals. The collective was important."

And he was right this was the peak of Brazil in the 21st Century, their crowning glory. Brazil were proud of their achievement and the team welcomed back as heroes, the discrepancies of the past forgotten, but as the old saying goes ‘pride comes before a fall’.

Scolari would leave after the World Cup and become Portugal's manager in 2003, meaning Brazil’s managerial roundabout began once again.

Zagallo returned as caretaker manager before Ricardo Gomes took charge of the national team as it entered into ‘Olympics mode’.

But for qualifying and the 2006 tournament, the manager would be Carlos Alberto Parreira, returning for his third spell in charge of the national team after winning the competition with Brazil in 1994.

Parreira had been a ‘silent and indirect assistant’ to Scolari in 2002 and after the win drafted up a technical report with a view to keeping Brazil competitive and retaining the title in 2006.

In 2003 he was named Head Coach with Zagallo as his technical director, and it seemed at first he was up to the task, with Brazil topping World Cup qualifying and avoiding a repeat of the torrid slog prior to the 2002 competition.

His formation of choice is 4-2-4. ‘Attack, attack, attack’ was the order of the day in a bid to recapture ‘Joga Bonito’.

Despite the top-heavy nature of the lineup and the forwards available to him (Ronaldinho, Ronaldo, Adriano, Kaka with Robinho on the bench), the team could not recapture the spirit of 2002 or 1998 going forward and never got out of first gear.

You couldn’t see it at first, Brazil dispatched their group of Australia, Croatia and Japan with ease. Ghana would also fall by the wayside in the Round of 16, being defeated 3-0.

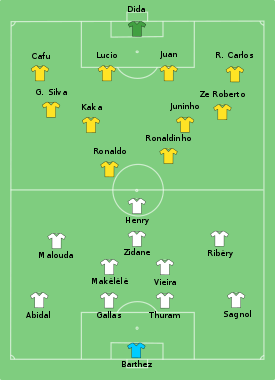

However then came an old enemy, France. Were the team that had stopped a back-to-back on one side of Brazil’s win ready to stop on the other side as well?

Well, yes.

Brazil lost 1-0 and the blame landed heavily on Parreira’s doorstep. BBC said of the tie in their post-match report:

Brazil had strolled their way to the quarter-finals, but Carlos Alberto Parriera's side had no answer to a France team that combined defensive discipline with some wonderful attacking play.

Parreira’s tactics were labelled outdated and he was shown the door. His previous win was all but forgotten, but such is the nature of football.

There is some credence in blaming his tactics, it did seem like the idea was to get all the best players on the pitch and hope they do the job, which removed the balance that Scolari had added with a number of water carriers.

However, some blame has to be put on the players both on and off the pitch. During the competition, reports began to circulate that the Brazil squad were allegedly more interested in Germany’s nightlife than their matches.

Given the reputation of players like Ronaldinho, Ronaldo and Adriano at the time, this doesn’t seem hard to believe.

Speaking in 2018, Kaka spoke of his disappointment with the result of the 2006 World Cup in an interview with SporTV in Brazil (luckily he had played 23 minutes in 2002 against Costa Rica, so had a winners medal to his name). He said wistfully:

"I think that the team could have done a little bit more. I think something was missing. Maybe we needed somebody to speak up. It was difficult to see that at the time but now, years later, you can analyze it and realize that it was a mess."

This would be the last World Cup for many of the golden generation. Cafu, Roberto Carlos, Ronaldo and Ronaldinho would all retire or fall out of selection by the time 2010 rolled around.

What had the potential of a Chicago Bulls-Esque three-peat ended up with a single World Cup to its name and things would only continue to get worse as the noughties rolled on.

The average age of Brazil’s 2010 World Cup squad was 28.6 years old.

For a squad that had just seen a number of its old guard make way, this seems particularly strange. Maybe it had something to do with Chekov’s ‘reduction of grassroots funds’ that I mentioned earlier.

Ramires was the youngest player in the squad at 23 years old; defender Gilberto was the oldest at 34.

They still had talent available to them with Kaka, Dani Alves and Thiago Silva but despite this, you couldn’t escape that this team seemed like a stop-gap between the golden generation and what would hopefully come next.

So how do you solve this sort of problem? Well, you can take the pragmatic approach and so straight after 2006, they appointed Dunga.

Dunga had been part of the Brazil team that had won the World Cup in 1994, and many of the values of that squad he had taken into his style of management.

Though the Selecao were celebrated once they brought the Jules Rimet back to Brazil for the 4th time, they did not have it easy along the way. After a loss to Bolivia in qualifying for the 1994 World Cup, they were labelled ‘dinosaurs’ and many fans bemoaned the football that Parreira was implementing.

However, they won and that’s what matters. Even one of the ‘great advocates’ of ‘attacking football’ Johan Cruyff (he was also pragmatic when he needed to be) said of their victory:

The secret of football is to keep control of the ball to pursue the goal. Only Brazil did it. For sure they could play more offensively and with more beauty, but there's moments when the spectacle has to be sacrificed."

So now he was manager, Dunga went about implementing a style of football that would help Brazil win games, whether it was considered ugly or not.

He implemented an asymmetrical ‘Christmas Tree’ formation, playing two defensive midfielders behind a trio of creative players and a striker. Though when the situation called for it he would use a ‘trivote’ (Jose Mourinho often used this for big games), playing a trio of three defensive players (note I say players not midfielders) to try and counter stronger opposition.

Dunga was the antithesis of the Brazillian football that had earned them the trophy in 2002. Tim Vickery would state in an article for Sports Illustrated:

Coach Dunga makes no concessions on the style debate -- he is on record as arguing that this obligation that Brazil has to play pretty soccer is nothing more than a European plot to ensure it never wins. His team can count on some dazzling individual talent, highlighted by the shooting of Maicon and Luis Fabiano in the opening two games. There is also no lack of goals.

But Brazil does not waste energy looking good. For long periods it can come across as labored and ordinary, with interplay and passing in midfield that is a pale shadow of the much-loved teams of the past. But it is big and strong, physically and mentally tough. The 2010 model might be difficult to love, but it is even harder to beat.

A 2-1 win against North Korea (yes the one where North Korea told their citizens they won 1-0), a 3-1 win against Ivory Coast and a 0-0 draw with Portugal saw them out of their group.

Pragmatism was prevailing and it would continue as they dispatched fellow South American hopefuls Chile 3-0 in the Round of 16.

But then they met the one thing they didn’t know to deal with, a mirror image; The Netherlands.

Their style of football under Bert van Marwijk was also ‘pragmatic’ (others would say dirty). They set out to stop the other team from playing their game with fouls and physicality. It was very un-Dutch in how much it ignored a lot of the Cruyffian values that they had built on for the past 30 years.

They also ‘did not waste energy looking good’, having ground results out against Denmark, Cameroon, Japan and Slovakia to get to the Quarterfinals.

The Netherlands would win the tie 2-0, thanks to a brace from Wesley Sneijder. Brazil were unlucky and actually played well, but Dunga had met his equal in style. However, where Brazil had tried to keep a small semblance of their identity intact, the Dutch had shed that side of their persona entirely.

Vam Marwijk’s team would go on to reach the final where they spent 120 minutes kicking Spain up and down the pitch, including an acrobatic effort by Nigel de Jong that planted itself firmly in the chest of Xabi Alonso.

They lost 1-0, and after the match, the man whose ideals they had so easily left behind, Johan Cruyff, had something to say about it in an interview with El Periodico:

"Holland chose an ugly path to aim for the title. This ugly, vulgar, hard, hermetic, hardly eye-catching, hardly football style, yes it served the Dutch to unsettle Spain. If with this they got satisfaction, fine, but they ended up losing. They were playing anti-football."

The sentiment stated here goes a long way to explaining why Brazil parted ways with Dunga after the competition. Playing ugly is all well and good as long as you come out the victors.

Dunga had learnt this in 1994 when he was hailed a hero, but he was experiencing the other side of the coin now.

So here we are, halfway through the century so far.

Brazil have one World Cup under their belt, but then in the next two appearances, they weirdly overcorrected in an attempt to win again; the first time trying to refind their ‘Joga Bonito’ spirit and the second abandoning it in favour of pragmatism.

However little did they know was the worst was yet to come, and on home soil no less…

Part 2 of Brazil - A 21st Century Breakdown coming next Friday…