Carlo Ancelotti: The Origin of 'The Eyebrow'

The series of unfortunate events that birthed a legend

“I cannot control my eyebrow. Sometimes when I see an interview with me I am really surprised about my eyebrow going up without control. But there is no reason for this, no accident behind it.” - Carlo Ancelotti speaking in 2017

As the clock ticked past the 89th minute in 2022, Real Madrid sat on the precipice of defeat.

Riyad Mahrez’s 74th-minute goal had put Manchester City two goals ahead on aggregate and Pep Guardiola was one step closer to leading his side to the final and potentially the first Champions League trophy in the club’s history.

Madrid hadn’t been awful across the two legs, but no one could argue as the clock ticked towards full-time that City weren’t worthy winners…but then Carlo Ancelotti raised his eyebrow.

Rodrygo scored in the 90th minute and then again in the 91st. Like a Nicolas Cage film from 2000, City’s guaranteed place in the finals was Gone in 60 Seconds, and now they were facing extra time.

Madrid saw their opponents were reeling and they went in for the kill. They attacked City relentlessly and then in the 95th minute they got their reward, a penalty kick. Karim Benzema was never going to miss and sent his team through to the final.

The internet of course did its thing and this emoji gained a new meaning:

Now it would be absurd to think that the majority of the players on the pitch could see such a small facial tic, even if the arch is so strong it looks like it could bend the fabric of space and time.

However, even if the movement of the Italian’s eyebrow doesn’t dictate whether Madrid wins or loses, the action has become symbolic of Ancelotti’s ‘laissez-faire’ or hands-off style of management.

But Ancelotti wasn’t always like this. If it wasn’t for events in his life, the famous eyebrow may have never come to be.

To understand the student, you must first learn about the man who gave Ancelotti his footballing education.

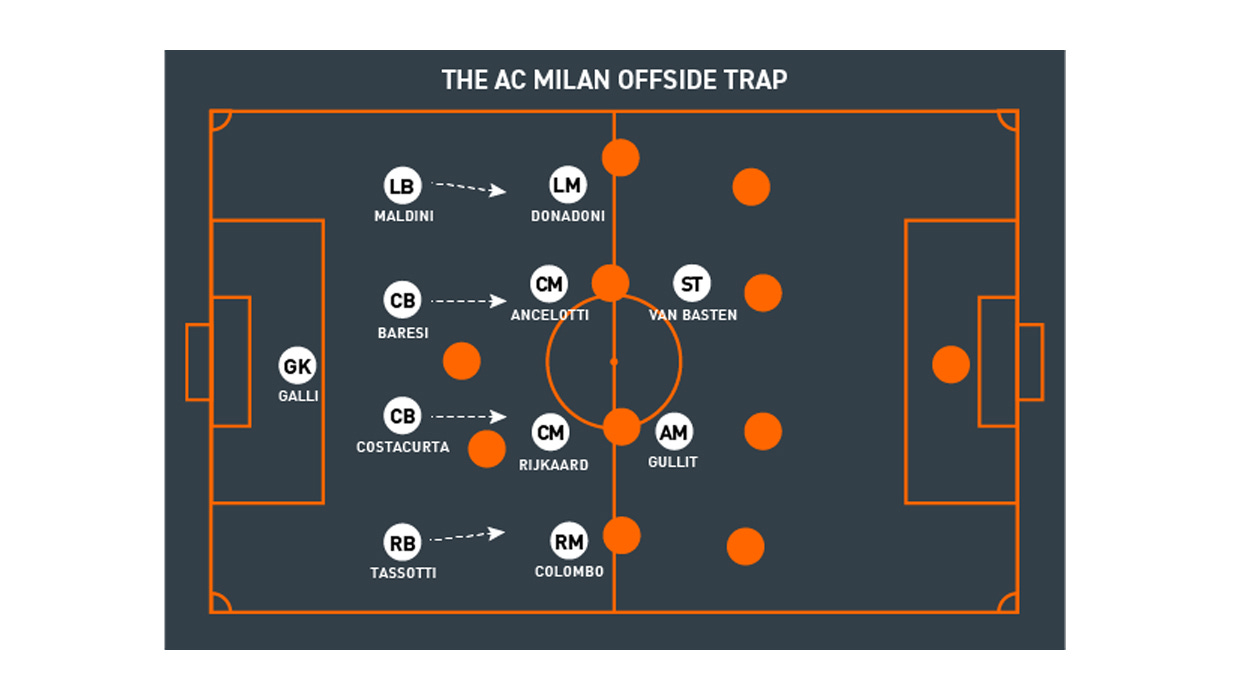

Arigo Sacchi was a legendary Italian manager who changed the face of football during the 1980 and 90s. His AC Milan side dominated Italy and then Europe with his own version of ‘Total Football’.

He believed that all players should be treated as equals, the team came before the individual at all times; individuality was sacrificed for structure.

A lot of the fundamental concepts he implemented during his time at AC Milan you can still see in the modern game - proactive defending, high structured pressing and a midblock with a high defensive line which sought to exploit the offside rule.

Sacchi spoke about the philosophy behind his ideas in his autobiography:

“The football I wanted was active also in the defensive phase. The players had to be protagonists through pressing.”

This was the environment where Ancelotti learnt his trade. He played under Sacchi for five years at Milan and when he retired in 1992 due to injury, he became his assistant with the Italian National Team.

Sacchi moulded the young manager into his perfect clone. In his first two jobs at Reggiana and Parma, Ancelotti would adopt the same 4-4-2 midblock as his mentor.

And he found some success. Under his guidance, Reggiana were promoted to Serie A in 1996 (he would leave before the commencement of the 96/97 season). He then would join his former club Parma and guide them to a second-placed finish in his first campaign.

However, his loyalty to the system that made him a great player blinded him to the changes he needed to make to be successful as a manager.

What Ancelotti needed was to be broken, he needed a crisis of faith. He required an event that would shake him so firmly to his core that his eyebrow would involuntarily raise for the rest of his life.

He needed Roberto Baggio to move to Bologna.

After coming second in Serie A with Parma, Ancelotti was presented with an opportunity to sign Baggio from AC Milan.

The then 30-year-old had been struggling for form during his final season with the Rossoneri; Uruguayan manager Oscar Tabarez had relegated him to the bench stating ‘there was no place for poets in modern football.’ He would regain his place for a short time but would be relegated back to the bench after hitting another dry spell.

After several poor results, Tabarez would be sacked and Baggio’s former coach and Ancelotti’s mentor Sacchi would be brought back to the club where he made his name to steady the ship.

However time had not made the heart grow fonder, and Sacchi also decided that Baggio was not part of his plans and Capello would agree when he became the permanent coach at the end of the season.

So Baggio needed a new club and Parma were eager to bring him in… but just because the ownership wanted the Italian superstar, Ancelotti would still need to be convinced.

Baggio had made his name as a number 10 playing behind the striker; this did not fit into Ancelotti’s 4-4-2 and when the Italian manager broached the subject with the player, the ‘Divine Ponytail’ was reluctant to make the change.

So the transfer collapsed and Baggio moved to Bologna. Ancelotti spoke about the transfer years later to the FA in an interview with The Boot Room:

“When I was at Parma I had the opportunity to buy Roberto Baggio who liked to play as an offensive midfielder behind the striker. I said to him ‘I want you to play striker because I don’t want to change the system’. It was a mistake because Baggio was a great player and I needed to find a position for him.”

Baggio would go on to score 22 goals and register 9 assists during his single season at Bologna, Ancelotti’s Parma would finish 6th and be unceremoniously knocked out of the Champions League and the Coppa Italia before the Italian manager was dismissed at the end of the 97/98 campaign.

You may doubt that not signing one player could have such a profound effect, but Ancelotti has mentioned the event on many occasions; it fundamentally changed how he viewed the game. He told Sky Sports:

“I finished my coaching career with 4-4-2 and then adopted that formation and didn't have the knowledge to go into other paths. I sacrificed the quality of the team for the system, but from there I changed my way of thinking. Now I adapt the system to my players because the most important thing is the player, not the coach or the game and now I have learned it."

This was the genesis point, the start of where Ancelotti began to diverge away from his Sacchian teachings. The foundations were still there but season after season he changed how he approached the game.

When he was appointed by Juventus, he broke away from his programming and changed his formation, allowing for different roles (even a player behind the striker). His transition was helped by the fact he had Zinedine Zidane playing as a number 10, but it was still a big shift. The Ancelotti of old would have forced him to play as a deeper midfielder, striker or even a winger.

Two trophyless seasons followed and Ancelotti was dismissed once again, his transformation into the trophy-winning machine we know today was not yet complete. His cold vibeless heart had begun to melt but it still needed thawing further.

Mayowa Quadri described it best when he referred to the Italian’s style of coaching as ‘the economy will regulate itself’; he picks the players and gives them the general idea of the system he wants them to play, but then it’s up to them to get the result.

This philosophy started to take a visible shape at AC Milan.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. When the prodigal son first returned to the San Siro, he managed a fourth-place finish and Champions League qualification but he came under fire from the club’s owner Silvio Berlusconi, which Ancelotti recounted in an interview to Die Welt:

“Berlusconi once called me in the middle of an TV show before an audience of millions to ask me why I played with one striker, saying ‘only communists play so defensively’? You have to understand that Berlusconi would only ever criticized me when we were playing well.”

This confused Ancelotti, but in some ways, it proved the catalyst for him to adapt his approach even further. It helped that this was the team he was blessed with:

(It should be noted that when you have teams of the quality that Ancelotti has had in his career, in general, it makes it a lot easier to take a laissez-faire, player-centric approach)

This is Ancelotti adapting the system to his players. For example, he moved Pirlo deeper to make the best use of his passing ability while flanking him with the energy of Gattuso and Seedorf.

Position-based tinkering is common throughout Ancelotti’s career, but instead of forcing players into positions in service of the system (like he tried to do at Parma), he now changes the positions to better suit the player’s strengths while minimising their weaknesses.

Pirlo was seen as a good creative midfielder who preferred to play further forward. He had incredible vision but he often couldn’t pull off the passes he wanted to.

This was due to the lack of space number 10s had thanks to many Italian teams still using a variation of Sacchi’s midblock and the player not possessing the dribbling ability of a Baggio or a Zidane to play around it.

Now Ancelotti can’t take all the credit for making Pirlo a deep-lying playmaker, during a loan spell at Brescia in 2001, Carlo Mazzone deployed him deeper to try and best use his long-range passing and ability to dictate the tempo of the game.

But if Mazzone was the one who put the idea out into the world, Ancelotti was the one who grasped it and made it Pirlo’s reality. Speaking in an interview with Gazzetta dello Sport years later, before the two met again in a Champions League clash, Pirlo was full of admiration:

"It's like rediscovering your father again. He changed my career, putting me in front of the defence. We shared some unforgettable moments. We had a magnificent past together."

At Milan, he lucked into a top-quality team that was underperforming; their drive was unquestionable, they just needed a different form of direction. They went from a manager who was trying to instil a philosophy in Fatih Terim, to a manager who was now letting them create their own.

Of course, the rest is history.

He won a Serie A title, a Coppa Italia, a Supercopa, two Champions Leagues, two Super Cups and a FIFA Club World Cup. This would be considered an impressive haul for an entire career, let alone just at one club.

This AC Milan team is one of my favourite teams of all time for good reason. They were incredibly fluid and every player who took the field for them was given the chance to shine, but I don’t think this is the pinnacle of Ancelotti.

That comes much, much later.

In his article ‘The Death of the Manager’ for Fansided, Jon Mackenzie states:

“All too often, we view [players] as products of a manager. No doubt managers play an important role in a player’s career. However, we often overlook the fact that players themselves can be the products of other systems.”

The team they play for, the occasion, and their individual personalities that have been cultured from their upbringing can be as important or even more important than who manages them.

Jon also states how something as simple as how a manager treats his players can affect them more than the odd tactical shout from the sideline.

Ancelotti at Real Madrid understands this more than most.

We have fast-forwarded now; past his time in the Premier League with Chelsea and in France with PSG, even his time at Napoli and (weirdly) Everton are a distant memory.

Ancelotti and Madrid are a match made in heaven. His approach to management blends perfectly with the club’s philosophy.

Rather than a controlling presence, he is a guiding hand. One of his main principles is that the team understands that he sees them as equals, but also that they see him as one as well.

After Madrid’s comeback against City, Toni Kroos spoke to DAZN about the special relationship that Ancelotti has with the players:

"The coach himself had a few doubts about who he would bring on and who not to bring on. We have all seen a few football games ourselves. That allows you to exchange ideas a bit. That describes him really well, and why things always work well with the team. It's outstanding. In the end, he decides, but of course, he's interested in our opinion.”

However, Ancelotti does make sure that the players understand the expectations of success and professionalism that the club and the fans have for them.

It helps that the experienced players in his team such as Luka Modric and Karim Benzema embody these principles as well. You will probably remember Benzema’s comment about Vinicius Jr that he ‘definitely’ didn’t say when the Brazilian could hear him on purpose (he says sarcastically).

Sometimes Madrid seems to forget their obligations, but the amount of comeback wins they have mustered now in the Champions League can not be put down to just luck.

Yes at times they may subscribe to the ‘diamonds are made under pressure’ manifesto, but as their games against Paris Saint Germain last season and Liverpool this campaign show, even when they go down by multiple goals you can’t count them out.

This is the true meaning of ‘the eyebrow.’ It is not a call to action, but a symbol of Ancelotti’s trust in his players to not disappoint themselves.

As the 63-year-old says, his eyebrow raise just happens and he expects it to happen, just as he expects that his team will get a result or at least put in a performance befitting their ability.

On the surface, the manager that you see before you now is unrecognisable from the man who stepped onto the scene at Reggiana almost three decades ago. But if you look close enough, you can see every lesson he learnt along the way.

The systems built around the players, the position changes to suit the individual and the culture of expectation that he can foster; these may not be the foundations but they are the pillars built on top that are holding up his dynasty.

Ancelotti has cemented himself in the pantheon of legendary managers, and while we should appreciate the managerial masterpiece that now stands before us, we should remember to pay homage to the early mistakes and original drafts that are still visible in the final image.

And what is that final image? Well, you already know:

Thank you again for subscribing to Played On Paper and I hope you are enjoying the paid content. See you next time!